|

What Do We Know about Lamanai?

The Lamanai Archaeological Project has enlightened us on the history of the Maya site of Lamanai in Northern Belize. As is always true of a large and long-lived community, the beginnings of Lamanai's 3200-year occupation history lie hidden beneath the accumulation of the centuries. Judging by radiocarbon dates associated with abnormally high concentrations of corn pollen in a feature called The Harbour, as well as dates from cores taken by a team from the University of Nottingham, the Maya had established an agriculturally based settlement at Lamanai by or before 1500 B.C. The concentration of pollen in The Harbour suggests very strongly that the material represents waterborne ceremonial activity in what was, probably throughout the site's occupation, a small arm of the great lagoon on which Lamanai faces. This in turn suggests that the settlement may have been of moderate size by 1500 B.C. There is a very small ceramic sample that is only a few centuries later in date, but the earliest extensive evidence associated with architecture, including both residential and communal structures, falls around 500-700 B.C., and reveals Lamanai as a nucleated community with a somewhat diffuse Central Precinct. By this time or slightly later, residential settlement had embraced what was to become the heart of the Classic-period Central Precinct, the area of Structure N10-43. High Temple Near the end of the Preclassic, probably around 100 B.C., a major transformation of the site took place. Whereas the community's centre lay originally in the northernmost part of the site as we see it now, probably to be near the small area of raised fields north of the site's margin, its Late Preclassic heart shifted southward. The shift embodied one of a series of truly major changes in Lamanai's appearance as well as its activity patterns. In a real "urban renewal" project, a group of small southern residential structures was supplanted by the massive initial stage of Structure N10-43, he High Temple, which served as the focal point for the first major plaza group to appear at the site. The pattern of a single dominant temple flanked and faced by markedly smaller buildings came to be characteristic of Lamanai's Classic development, and may in some senses have persisted throughout the remainder of the site's occupation. As was also the case with earlier Preclassic structures, N10-43 saw some measure of the dedicatory cache deposition that was characteristic of most Maya construction. However, as remained true for the full course of the site's history, the number and splendour of the caches was limited in comparison with sites such as Altun Ha, some 40 km to the east. At about the same time as the building of N10-43's first stage, a complex three-structure group atop a platform, probably set in turn on a larger platform, came into being as the start of what ultimately grew into the N9-56 group (the Mask Temple). Mask Temple N10-43 continued as a principal element during the Early Classic, and during this time the multi-structure N9-56 group began to take the shape that it was to retain throughout the Classic. In contrast with the relative poverty of dedicatory material in both settings, N9-56 and its supporting platform became the sites of two comparatively rich tombs. Beneath complex hoopwork domes, which were covered in coarse textiles that were in turn swathed in fine textiles soaked in red pigment, the occupants of the two tombs lay surrounded by wooden objects, pottery vessels, and a variety of jade and shell mosaic ear ornaments and apparent pendants, among other artifacts. Luckily the vessels, Early Classic Tzakol 3 polychromes, fix the dates of the two tombs near the beginning of the sixth century A.D., but unluckily neither ceramic nor other evidence tells us which tomb preceded which. The issue is particularly important because the occupant of Tomb N9-56/1 is male and the individual in Tomb N9-53/1 is female. The most interesting aspect of the two tombs is the difference in their location. Tomb N9-56/1 lay in the heart of the temple, on its midline, a highly honorific position. Tomb N9-53/1, in contrast, lay in a pit dug into bedrock and covered by an element of the front of the large platform on which N9-56 sits. Both its association with a subsidiary platform rather than the principal temple and its position far from the platform's midline make the tomb appear less important, but form and contents convey the opposite message. Jaguar Temple At about the same time as the construction of the two tombs, or perhaps slightly earlier, came the beginning of the southernmost plaza group in the Central Precinct, dominated by Structure N10-9 (the Jaguar Temple). This plaza and the assemblage of buildings raised on a high platform at its northern border, known today as the "Ottawa" group, appear to have become the main focus of Lamanai public life during the Late Classic. In its original form the group consisted of two plazas at different levels, bordered by residences and buildings that probably saw combined residential and administrative use. By this time a distinctive form of construction known as the Lamanai Temple Type had come into being. The type is characterized by the absence of a chambered building at the platform top and the presence of a long, narrow chambered unit set athwart the central stair, usually about one-third of the distance from the platform's base to its top. The Lamanai Temple Type is exemplified by the middle construction stages of N10-9, as well as by Late Classic modifications to N10-43, to other buildings in the N10-43 plaza group, and in some measure by changes to N9-56. More than the ceramics or other artifacts from the site, the distinctive temple type serves to identify links with other centres in the area; a single example, Structure B-4/7, is known at Altun Ha, and one is reported also from Chau Hiix, which lies almost exactly halfway between Altun Ha and Lamanai. The Terminal Classic and "Ottawa" Group, Plaza N10[3] Among the site's many significant features, perhaps the most important is Lamanai's history as the Classic came to an end. Whereas neighbouring sites proceeded through a period of decay to final collapse of sociopolitical structures in the ninth and tenth centuries, Lamanai survived this time of upheaval, and lived on into the Postclassic. There is, in fact, very good evidence that the people of Lamanai exerted one of their greater efforts in construction in the Terminal Classic period. Towards the end of the 8th century, a huge transformation of the Ottawa group began that occupied decades, and may have involved the amassing of more than 20,000 metric tonnes of building material. We are still in the process of sorting out the construction sequence during this period, but it is clear that most of the Ottawa group in the Terminal Classic comprised low masonry platforms that supported wooden superstructures; the exception was N10-15, additions to the north of which were of masonry construction. The Late Classic plaza itself was completely filled in, and the plaza surface raised to above the level of Late Classic platforms. By the end of the Terminal Classic, the focus of life at Lamanai had shifted very strongly southward, and during the centuries of the Terminal Classic (ca. A.D. 800-1000) a revamped area east of N10-9 had been combined with the drastically modified "Ottawa" group to make up a new, reduced Central Precinct. Whether population had declined by this time is not clear, but it is abundantly clear from the archaeological evidence that the restructured community continued to thrive, that waterborne commerce intensified, and interchange with Peten communities diminished to make way for increasing links to communities in the northern part of the Yucatan Peninsula By the 11th century, modification and maintenance of most or all of the buildings in the northern part of the Central Precinct had ceased, and some buildings may already have begun to disintegrate. The Jaguar Temple, N10-9, however, continued to be modified on its plaza-facing side; low platforms supporting wooden superstructures were built in the Ottawa group; and habitations sites clustered along the lagoon shore. The Postclassic By A.D. 1200, and possibly as early as the late 10th-early 11th century, copper-tin bronze objects, primarily bells and clothing ornaments, had begun to flow into Lamanai from sources in West Mexico, the Oaxaca Valley, and probably middle Central America. Out from Lamanai to the coast and to other towns in Belize went a distinctive style of ceramics, and probably other goods and ideas as well. Lamanai, in fact, seems to have filled the vacuum left by the decline of Chichen Itza. The ceramics, defined at Lamanai as the Buk Phase, are classified typologically as Zakpah orange-red and Zalal Gouged-incised. In addition to a great variety of tripod and some tetrapod forms, Buk vessels include complex censers and a distinct kind of pedestaled dish—used, we think, to burn incense—to which we have given the name "chalices." From about A.D. 1000 onward, the centuries of the Early Postclassic are quite likely to have been a time in which the Lamanai community saw immigration of people from the fringes of nearby centres that were undergoing gradual abandonment. Unfortunately but quite expectably, the archaeological evidence does not show how the inhabitants of Lamanai dealt with a surrounding Southern Lowlands world on which the aftermath of the Classic collapse continued to tighten its grip. Ties with Ambergris Caye, however, suggest that trade and commerce remained lively. The picture of Lamanai in the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic seemed at first to be of an island of relative calm in a sea of chaos. Beginning in 1986, and resumed in 2010, work on Ambergris Caye has shown that in these same centuries at least one other settlement--Marco Gonzalez at the southern tip of the caye—continued to flourish. During the Middle and Late Postclassic, however, the focus shifted from Marco Gonzalez to a community that was located where the modern town of San Pedro now stands. Marco Gonzalez’s prosperity during the Early Postclassic appears to have stemmed at least in part from close links with Lamanai, documented by the presence of masses of Zakpah and Zalal pottery, much of it with distinctive proportions and decoration that indicate manufacture at several communities in northern Belize. Later in the Postclassic, Lamanai appears to have shrunk even further into its southern focal area, but material-culture innovations continued, especially in ceramics, as presumably did trade with centres farther to the north. Throughout the centuries of the Postclassic, Lamanai's inhabitants not only continued modification and maintenance of the front of the Jaguar Temple, Structure N10-9, but also retained an attitude of reverence towards decaying structures farther north. By about A.D. 1300 or a bit earlier the residents of Lamanai had begun to make offerings in the ruins of northern Central Precinct buildings, usually by burying vessels in collapse debris, on or near the primary axis. Between A.D. 1400 and 1450 they—or possibly even visitors to the community—undertook one of the larger ritual offerings in the community's history in just such a decaying temple setting, surely a sign that the ancient scenes of religious activity were still seen as places of great power. Atop Structure N9-56, a huge quantity of figural censers, generally known as Chen Mul Modelled, were smashed and scattered. The number of vessels, perhaps as many as 100, and the symbolic content of the objects combine to bespeak the truly major importance of the event. Near the time of the great offering, but whether before or after it we cannot say, the Maya removed a carved stela from some other location and re-erected it in front of N9-56. Together with this effort came the construction of a group of very small platforms at the foot of N9-56, and the tiny buildings also served as sites for offerings that included miniature human or deity-figure vessels. In this same period, construction was proceeding in the Postclassic Central Precinct, and probably in scattered locations elsewhere around the site as well. Metal working and the Hunchback Tomb As the Postclassic progressed, the citizens of Lamanai imported Red Payil Group ceramics from somewhere along the coast of Quintana Roo, and appear to have been receiving objects from central or southern Mexico as well. Around the turn of the sixteenth century Lamanai’s potters developed a new style of ceramics, during the Yglesias Phase. At about the same time Lamanai's inhabitants took a significant technological step forward by beginning to work metal. Previously unknown in the Maya area, the casting of bronze objects became part of Lamanai's cultural array with the production of bells, rings, needles, axes, and other forms. Analysis of the objects shows that the metal used in their manufacture was produced by the melting down of artifacts, almost certainly part of the inventory imported in earlier centuries. The community's strength is reflected by the early sixteenth-century burial of an individual who may have been the last prehistoric community leader (“The Hunchback Tomb”); the interment was attended with the same level of richness that had marked the interments of his mid-Classic predecessors. Maya Churches Evidence both documentary and archaeological suggests that the Franciscans first set foot on Lamanai's shore about 1543-44. In the succeeding century a zone well south of N10-9, which had been transformed into the community's heart by or before 1500, felt the winds of change once more as the European presence inserted Christian churches and related structures into the indigenous settlement pattern. As in many other places, the Spaniards supplanted what was probably the principal ceremonial building of immediate pre-Contact times—a Tulum-type temple—with a Christian church (YDL I) that closely resembled the one known at Tipu. In the course of the demolition and new construction, one of the Mayas apparently sought to copper his bets with the ancient gods by placing a small animal-effigy vessel offering in the remains of the soon-to-be-concealed Maya temple. Another effigy, combining traits of a centipede and a lobster, was cached just north of the church’s northside stairs. This distinctive local appropriation of Christian sacred spaces presumably characterized Lamanai from this point onward. Later, perhaps late in the 16th century, the first church was supplanted by a much larger and more permanent structure, YDL II, erected immediately to the north of YDL I. The larger church, YDL II, suggests ambitious Franciscan plans for Lamanai, which appear never to have been realized. Like the first church, YDL II had locally made objects, mainly effigies, cached in key locations within the nave and sanctuary. Two stelae were also at some point re-erected in the nave, although this likely took place during or after the years of open resistance (see below) when both the regular and secular clergy had abandoned their visits to Lamanai. For nearly a century the Spaniards held sway over Lamanai despite the fact that their presence there was only intermittent. Christian worship was led by a visita (circuit-riding) Spanish priest whenever he could be present, but otherwise was probably presided over by a native sacristan. A cacique (native leader), whose home we believe we discovered during excavation, was probably the lone voice of Spanish secular control whenever no Spaniard was at the site. In his home the cacique held numerous European utilitarian objects, ranging from a steel axe and two knives to a variety of other pieces of metalwork, which were symbols of his status as much as they were useful tools. In addition, he possessed or served as custodian of two books, of which the only evidence we recovered consists of two portions of gilt bronze hinges. In the 1630s rebellion broke out among the southern lowlands Maya, and when Fathers Bartolomé de Fuensalida and Juan de Orbita arrived at Lamanai on their way to Tipu in 1641 they found the second church and its outbuildings burnt, and the people supposedly decamped to join the rebels centred at Tipu. Though the Spanish perception was that Lamanai lay abandoned, in fact the Maya returned to occupy the colonial-period centre, including the area of the churches, for what may have been more than a century. One of the caches in the nave of the second church, possibly buried during these years if not earlier, consisted of a group of miniature human-head vessels, probably incense-burners, and another was a large bicephalic crocodilian effigy. Together with other images with highly unusual anatomical features, such as the centipede-lobster effigy from YDL I, the church offerings document a resurgence of Maya iconography, which in fact had probably never been fully suppressed in the time of Spanish contact. At a later time, probably when ceremonial activity in the church zone had come to an end, a Maya family moved into the sanctuary of the second church, and for a considerable time deposited rubbish around the building's perimeter. Identifiable Maya presence at Lamanai remains elusive for the bulk of the 1700s, although recent investigations focused on the British colonial period may in time fill this gap. Given the resources of the lagoon and surrounding land, it is highly unlikely that the Maya left this area vacant during the 18th century. The 19th and 20th centuries at Lamanai The historical-archaeological analysis of the British plantation settlement (1837–1868) at Lamanai is an ongoing project (begun in 2009), which is designed to study the patterns of relationships among people, materials, and space active during the nineteenth century at Lamanai. The project centers on the recovery, analysis, and synthesis of artifact and feature data from different areas of the nineteenth-century British plantation estate at Lamanai. These data have been used in tandem with documentary information to understand more fully the realities of day-to-day life during the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century for the residents of Lamanai. During the nineteenth-century, power between indigenous and European groups in Central America and Belize (which went from being called the Bay of Honduras to Honduras and later British Honduras) was experiencing rapid change driven by many factors. The abolition of slavery increasingly commodified labour, which was already a scarce resource in Central America and a necessity for industrial endeavours such as plantations. Control of trade ports and river routes was moving from the Spanish to the British and Central American governments. The hunt for natural resources to exploit in what is now Belize, such as mahogany and logwood, was driving colonists deeper and deeper inland as these resources became scarce along the coasts and inland rivers. It is likely that legitimate British colonists arrived at Lamanai in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, or earlier, and abandoned the site in the last quarter of the century, but no records of formal occupation exist until 1837, when two hundred acres of land were purchased by Hyde, Hodge, and Co. in order to plant sugar cane and build a sugar mill at the site. The sugar mill was not in working order until 1860 and only remained a working sugar estate until approximately 1875. Recent excavations (2014) at a residential site near the New River Lagoon, south of the main Lamanai city center and north of the Spanish churches, recovered artifacts such as bottles, pipes, ceramics, architectural/construction objects (e.g. nails), and food remains (e.g. chicken, cow, and pig bones) that date to the mid-nineteenth century and possibly earlier. Interestingly, objects dating to the 1980s and early 1990s were also recovered, which led the team to find a local individual whose family lived at the site until 1992. The final chapter in the site's history, prior to commencement of the Royal Ontario Museum's excavations in 1974, was an attempt at sugar production from about the 1850s to the early 1880s. The Belize Estate and Produce Company (BEC) carried out logging activities in the 20th century, but the details remain to be explored. The start of excavations in 1974 marked the emergence of Lamanai as a site for which we can now trace the outlines of a Maya history that stretches from 1500 B.C. to the present, probably the longest known unbroken span of occupation in the Maya world. Excavations at Lamanai over the years (1974 to 1986; then 1998 to the present) have been sponsored by the Royal Ontario Museum, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, National Geographic Society, York University (Ontario), FAMSI (Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studied, Inc.), University College London (UCL), the Institute of Archaeology (UCL), the British Academy, and the Friends of Lamanai. |

Central Precinct, south

High Temple, N10-43

Late Preclassic 100 B.C. Mask Temple N9-56 Preclassic

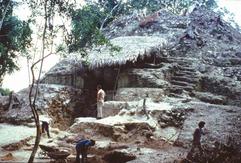

100 B.C. - A.D. 450 Mask Temple during excavation in 1977,

south side mask still covered by terraces and stairs of earlier phases Humming bird dish d: 38 cms

Early Classic Tzakol 3 Mask Temple Early Classic c. A.D. 500 Tomb N9-56/1 Jade necklace Mask Temple Tomb

Early Classic c. A.D. 500 Tomb N9-56/1 High Temple Late classic A.D. 600-700

Jaguar Temple N10-9

Jaguar Temple Late Classic A.D. 500-600

"Ottawa" complex N10 [3]

Buk phase pedestal-base jar

Early Postclassic 1100-1350 A.D. Pedestal-based "chalice" vessels. Early Postclassic, from Jaguar Temple

Postclassic Chen Mul figurine found smashed at base of Mask Temple

Mask Temple in 1980 with stelae erected in the late Postclassic

Cib phase pedestal-base jar

Payil Red, Late Postclassic c. 1300 A.D. burial N10-4 46 Copper ring and bell found in the area north of the Churches

Hunchback figurine H: 30 cm

Spanish colonial period, YDL I in foreground, built around 1543, chapel of YDL II in background

Double headed shark/crocodile figurine

L: 23 cm Centipede/Lobster figurine found north side of YDL I L:21 cm

Sugar Mill built by the British in the 1860s

Condiment Bottles H: 12-15 cm

Gaudy Welsh chamber pot D: 26 cm

Below: wine bottle |